Earlier this year, on March 1st, I joined a Zoom call to watch sociophonetician Dr. Nicole Holliday (from UC Berkeley) talk about “Sociolinguistic Challenges for Emerging Speech Technology,” and I walked away with some pretty interesting insights into how data and machine learning can be more ethically used in speech applications. The lecture was recorded and posted at this link for anyone who wants to watch it for themselves.

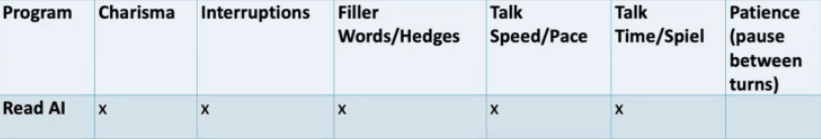

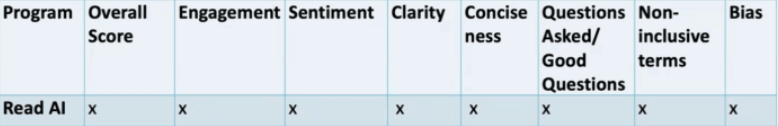

The part that I remember most vividly about her lecture was when she was analyzing issue’s with Read.AI’s “Speaker Coach” services. Essentially, these are services provided by Read.AI (an SPST – Socially Prescriptive Speech Technology) in which artificial intelligence is used to “judge” a human speaker’s speaking ability, either by studying a person giving a presentation, leading a meeting, or doing another speech-heavy activity. This is all sounds pretty good…on paper. But in practice, Read.AI tends to over-generalize what the desired qualities in a good speaker actually are. What this comes down to is a fundamental flaw in how their model is processing the linguistic data they collect about speakers.

Let’s walk through some of the data Dr. Holliday presented during the lecture.

Read.AI’s scoring criteria emphasizes low use of “filler words” and “non-inclusive terms”

The problem with taking off points for speakers using filler words/hedges like “ah, um, and hmm” is that these words are actually best used in moderation, meaning using too many fillers and using too few fillers both make a speaker sound less credible. Using too many fillers makes a speaker sound unconfident in their topic. But on the other hand, using too few fillers makes a speaker sound robotic and unrelatable to their audience. So, an important balance to strike in public speaking is to use just the right amount of fillers, because at the end of the day, filler words show your human side.

In one sample, however, Read.AI categorized 99% (87/88) of individuals as having a “high” level of filler words, regardless of their actual rate for filler words per minute. So, why is Read.AI over-emphasizing the negative aspects of filler words, and in doing so, completely ignoring an important nuance about public speaking? (By the way, the overvaluation of one metric over others in data science is considered confirmation bias, which is a very dangerous practice that should be avoided.)

Furthermore, the problem with taking off points for speakers using non-inclusive terms is that what is and isn’t “inclusive” is highly subjective based on the culture in which you work. For example, the second person plural pronoun “you guys” is considered a non-inclusive term by Read.AI. But where I come from, there is nearly nobody I’ve talked to who’s been offended by someone saying “you guys,” and Dr. Holliday notes the same to be true for where she lives as well. This shows that Read.AI’s model is not contextually calibrated across cultural or regional language norms. In data science terms, this is a reminder that even the most advanced algorithms can amplify bias when they treat social nuance as universal data.

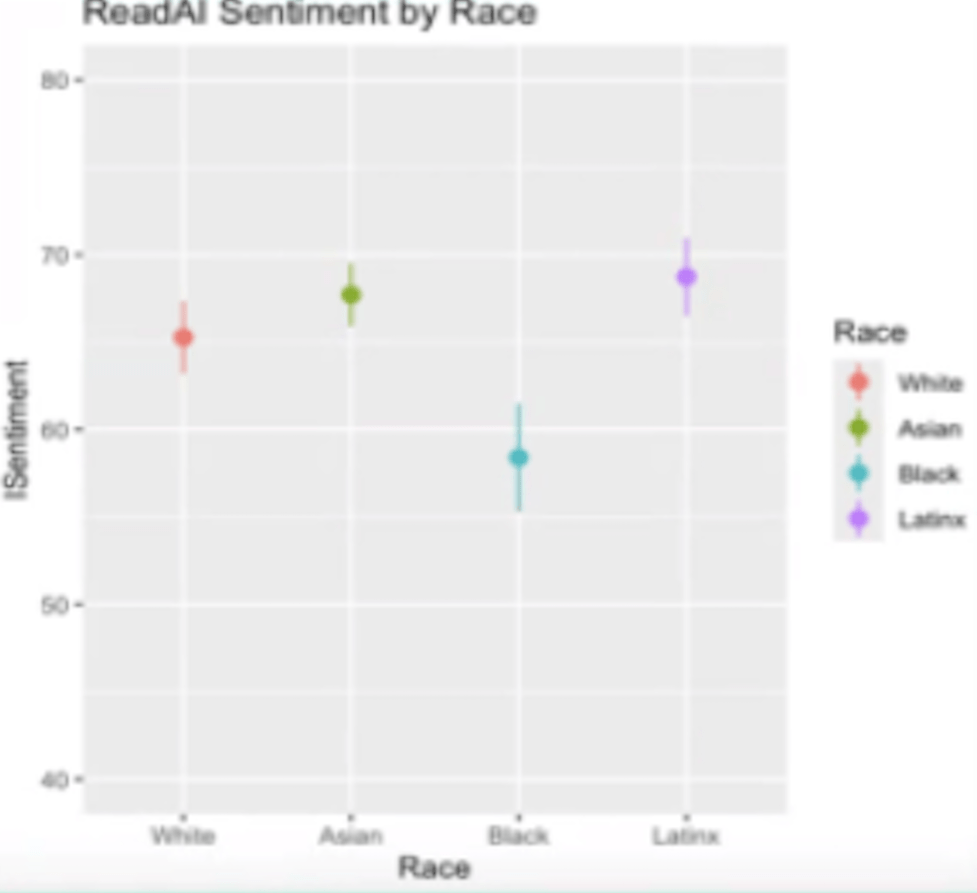

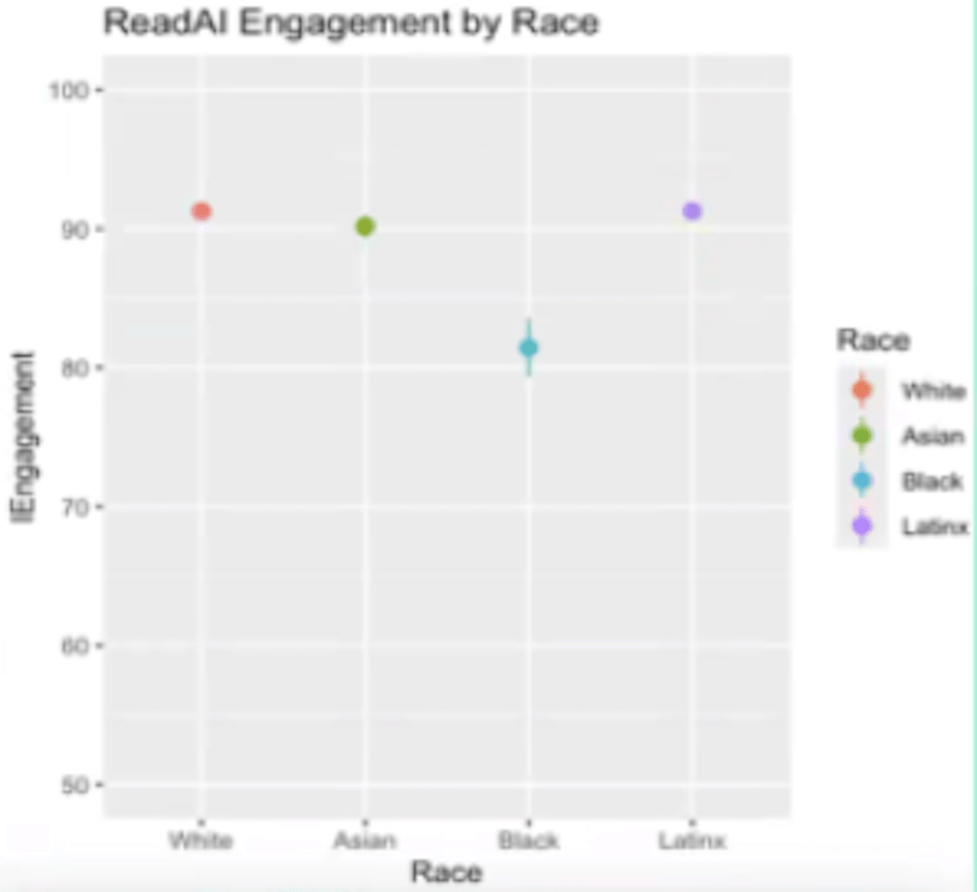

Read.AI’s sentiment and engagement results by race

Read.AI downgrades sentiment scores for Black participants by about 8 points relative to the baseline. Similarly, it downgrades engagement scores for Black participants by about 13.9 points relative to the baseline. Both of these metrics show systematic disparities that point to potential demographic bias in the model’s evaluations. As Dr. Holliday puts it: “LLMs are Biased, so SPSTs are Biased!”

My conversation with Dr. Holliday over email

After the lecture, I emailed Dr. Holliday asking her what developers can do to reduce these sociolinguistic issues while still improving accuracy and efficiency, and she was super kind and helpful in her response! In her reply, she explained that the main issue lies in how these technologies are marketed and utilized—that companies like Read.AI should be more transparent about how they train their model and allow researchers to test systems to make them more ethical.

As someone passionate about data science and machine learning, Dr. Holliday’s lecture made me realize that the future of speech AI depends not on how fast it learns, but on how well it listens.

Leave a comment